I find the importance that we place on book covers these days pretty fascinating. I’m as guilty as anyone else. A book with an amazing cover definitely turns my head. Though I’d certainly never buy or borrow a book on the strength of its cover – recommendations from people I know or whose judgment I trust are still what drive the majority of my decisions to read something or not – I’m aware of the little edge that a good cover can give a book. In fact, I was reading an excellent piece on this not very ideal state of affairs, recently, in It’s Nice That, on whether, in this social-media-heavy age, judging a book by its cover has gone too far?

As an author and translator, I feel this state of affairs acutely. I’ve been fortunate enough to have some very marvellous covers grace my own books. The cover for The Majesties was a semi-finalist for Electric Literature’s annual Book Cover of the Year Tournament in 2020. The cover for my translation of Budi Darma’s People from Bloomington was designed by none other than the Tom Gauld. I’ve been in this biz long enough to know the rush you get when your editor reveals the cover to you, and you LOVE. And also what it’s like to open the attachment and regard a book cover design, and think, It’s all right, I guess. Or worse: Oh no.

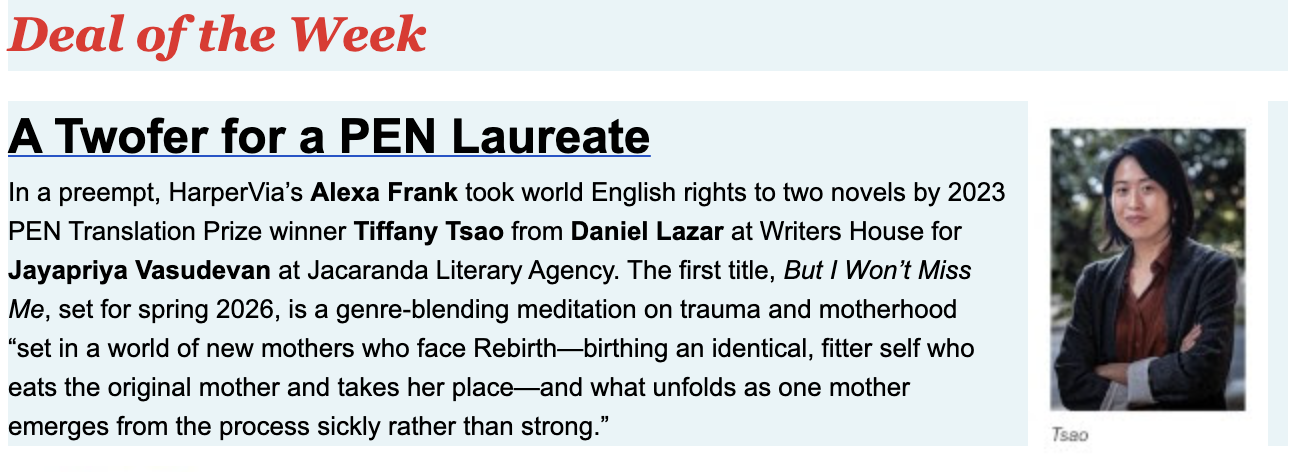

So when my editor at HarperVia sent me the cover design for my upcoming novel But Won’t I Miss Me, I breathed a tremendous sigh of happiness and relief. It was LOVE at first sight. I opened the email on the Sydney Metro, after dropping my kids off at school, and I broke into such an enormous and sustained grin, the people around me must have thought I’d just received a love letter or something.

This is the cover, designed by Stephanie Shafer. Her note on the design will appear in the book itself, but here is a excerpt:

The photograph, with its translucent veil and interior light, suggests both a womb and a shroud. The pink light evokes life and warmth but also danger—flesh turned alien. The goal was to create a cover that feels beautiful but uneasy […]

Turning now from sights to sounds: I was pleased to participate in a series on literary translation for The Critic and Her Publics podcast, hosted by Merve Emre in conjunction with The New York Review of Books, Literary Hub, and the Hawthornden Foundation. This particular series of conversations makes up Season 3 of the podcast, and was released just a few months ago. Here’s the description:

In 1999, twelve distinguished writers gathered at Casa Ecco, a villa on Lake Como, to discuss the art of translation. Twenty-five years later, their ideas are still apt and powerful. Last October, Merve Emre convened a group of translators and publishers at the same villa to return to those ideas and to examine a field at an inflection point.

In this series, you’ll hear from the translators Maureen Freely, Daisy Rockwell, Virginia Jewiss, Jeremy Tiang, and Tiffany Tsao, as well as publishers Adam Levy (Transit Books) and Jacques Testard (Fitzcarraldo Editions).

The podcast is available to listen to on Apple, Spotify, and other venues. My personal favourite moments: talking about the importance of first sentences; Frankenstein’s monster; shame as occupational hazard for a literary translator; and the money aspect (grimmish).

My recent essay for Griffith Review, “Grave Years and the Undead Woman,” is now available to read for free, in its entirety, on the essays page of my website. This is due to the exclusivity period being up, which means I am now free to publish it here!

It’s been very encouraging to see receive so many positive responses from readers of the essay in GR itself and in its pdf form, most of them mothers – and many who are also writers – who have had similar feelings, experiences, and thoughts.

Some other good news, which I’ve known about for some time, but have been unable to share until recently: a co-translation, coming out in August next year! The English-language edition of Intan Paramaditha’s novel Night of a Thousand Hells (Indonesian title: Malam Seribu Jahanam) will be coming out in August next year with Scribe in Australia and Europa Editions in the UK and US, as translated by Stephen J. Epstein and myself. There was an announcement in The Bookseller, but I’d also like to thank my agent, Jayapriya Vasudevan of Jacaranda Literary Agency, who is not mentioned in the article, for representing Stephen’s and my interests as translators.

Stephen has been working with Intan for years, translating into English her short-story collection Apple and Knife and her novel The Wandering. I’ve been cheering them on for a long time, and was pleased to be invited on board to collaborate with them on the English-language edition of Intan’s very fantastic most recent novel. By good luck, Stephen happened to be passing through Sydney for a few hours on his way home to New Zealand, and he, Intan, and I got together for a celebratory lunch the day before the announcement was made. Here we are in Central Station on Gadigal land.

Somehow, between all the text-wrangling and reading-for-work, I’ve been managing to find time to read for leisure. Recent books include:

Translation is a Mode = Translation is an Anti-neoclonial Mode by Don Mee Choi (A slim genius pamphlet. Brilliant.)

Cannon by Lee Lai (A graphic novel. Inhaled it and felt out of breath. So many feelings.)

Theory and Practice by Michelle de Kretser (A novel. Straightforward and elegant.)

Where Reasons End by Yiyun Li (A novel. Heartbreaking.)

Paya Nie by Ida Fitri (A novel set in Aceh during the conflict – a window into women’s lives and a community, and the hardships they must endure.)

Hope you’re finding time to read for leisure, and pleasure, as well!