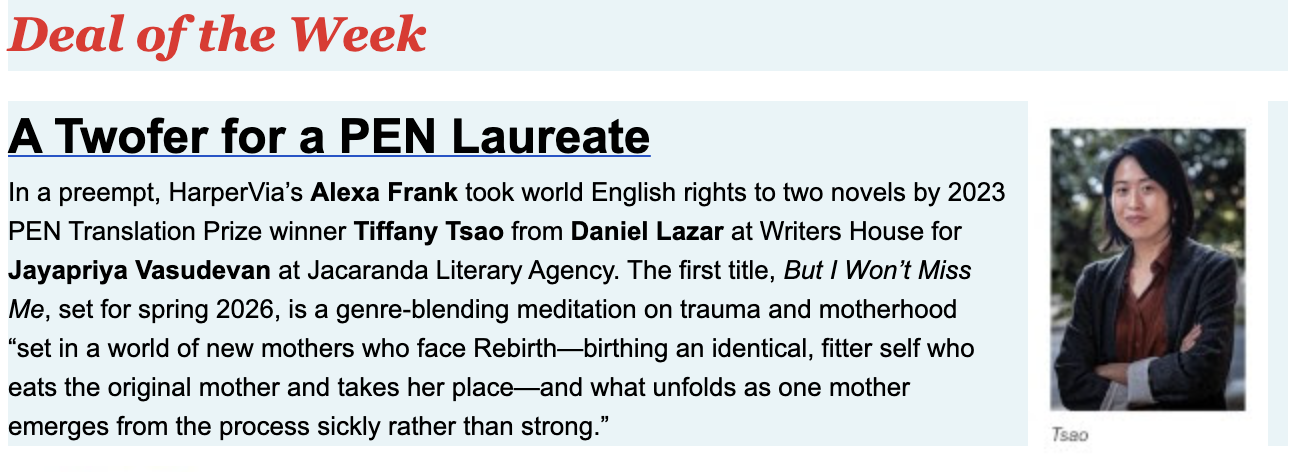

Good day to you, handful of readers of this blog! I would like to present, proudly, an excerpt of the manuscript of Book 3 of the Oddfits trilogy…all of which is still looking for its new home. (Long story. I’m a bit tired of recounting it. But I have to say, I am still so proud of all three books, for which I hope my agent will find a home someday!)

The following is from a chapter early on in the book. Please enjoy! (said Tiff, trying not to feel secretly despairing that it’s been almost a year since she finished the manuscript for this third book and is still seeking a home for the whole trilogy, even though she is a published author so one would think this would be easier, and even though she’s a prize-winning translator, so, really, her ego should be wonderfully plump, but there you have it.)

From Chapter 5 of The Disordered Spring (forthcoming, I’m sure)

Murgatroyd couldn’t afford most things these days, so the one thing he genuinely couldn’t afford was to be late for work. Especially since he was planning to ask his new boss for more hours. He sprinted past Melt My Butter Café, rounded The Fattened Calf steakhouse on the corner, and shot up the stairs two at a time, before scurrying quietly past his former place of employment—The Obese Mouse—into his new one, Pasteural. The professional hedge-trimmers that saw to the semi-weekly upkeep of the topiary signage out front were just finishing up. Murgatroyd smiled awkwardly at them as he slowed to a trot and, panting, parted the dense entrance fronds and stepped into the interior.

Preparations for the lunchtime crowd were already in full swing. The dining room floor had just been mown, and the air was heavy with the fragrance of freshly cut grass. The tables and chairs had already been draped in new lawn coverings, and the place settings—wooden dishes, cutlery, and cups of a delicate rough-hewn appearance—were being laid out by Murgatroyd’s co-workers, all of whom he barely knew because he’d only started working there last week.

Murgatroyd had just made it across the main dining room to the staff area in order to change into his waiter’s caftan when a loud gurgling sound made him jump. He turned to see the small pond in the middle of the dining area filling up with blue water. He recalled what Mr. Harry had told him last week when giving him an orientation: the pond water was turned on at 11:30am. Which meant he was half an hour late.

“You’re half an hour late,” confirmed an American-accented voice behind him.

Murgatroyd yelped and turned. It was Harry Jones, the owner of Pasteural, shaking his head in disapproval. If it were possible, his carefully trimmed stubble and rumpled flannel shirt seemed to only augment his severe demeanour.

“Sorry, Mr. Harry,” blurted Murgatroyd. “I promise it won’t happen again.”

Harry stared coldly at Murgatroyd. “Yes, please see that it doesn’t. Not for my sake, but that of our guests. How can you care for them as they deserve if you don’t even arrive on time?”

“Erh, I…can’t?” ventured Murgatroyd timidly. Leaving rhetorical questions unanswered had never been his strong point.

Harry exhaled impatiently. “And another thing. It’s not ‘Mister Harry.’ Just call me Harry. I insist on being approachable.”

“Ah, yes. Sorry. Sorry, Mr. Harry. I mean, Mr. Jones. I mean, Harry. Yes, Harry, sir.”

With a look of withering contempt, Harry waved Murgatroyd away.

In the staff bathroom, as Murgatroyd changed out his T-shirt and Bermuda shorts, he gazed at the toilet bowl and somehow felt it reminded him of his life. The excitement of that morning had afforded him some respite, but now his misery was back—not just a feature of his existence, but the very stuff of which it was made. After all, hadn’t this been what he’d been doing twelve years ago, when Ann had found him and invited him to join the Quest: waiting tables at a fancy restaurant for a not-very-nice boss? And when you thought about it, wasn’t it worse now? Back then, he hadn’t known he was miserable, and therefore, he had believed himself to be content. Back then, he had at least clung to that promise: Something stupendous is waiting for me. Now he was on the other side of that stupendous something—he’d had it and held it. Then it had melted away. There was nothing to hope for anymore, nothing better to look forward to. How he missed exploring. And how he missed Nutmeg and Tremble most of all.

As he slid his head into the noose of the caftan’s neck, and his arms into its sleeves, he felt a familiar sensation take hold of him, rolling back his shoulders, straightening his spine. It was the transformation that used to come over him every night when he waited tables at L’Abattoir in the Known World. It had been the one thing he had been good at. Truly, nothing had changed.

He strapped on his leather sandals, stowed his clothes and flip-flops in his employee cubbyhole, and glided out to the dining area to join the rest of the staff, newly clad not just in caftan, but elegance and poise. The artificial lake was now full, the tables were all laid, and the daily staff briefing was about to begin.

One of the other waiters tapped Murgatroyd on the shoulder.

“How did you do that?” she whispered enviously.

“Do what?”

“You know. Become not you.”

Harry cleared his throat and his employees fell silent. Murgatroyd remembered what Harry had said to him while hiring him last week: Pasteural is not just a restaurant. It is a life path. It is a religion. I only ask that you serve it with all your heart and soul. Do you think you can do that—give it your whole heart and soul?

Freshly fired from the restaurant next door and bereft of other options, Murgatroyd had had little choice that day but to say yes.

“Good day to you, my fellow shepherds,” Harry began. And here, he stretched out his arms as if he had read somewhere that this was a gesture of warm camaraderie. “Today is a truly momentous occasion for we members of the Pasteural community. Today, Pasteural officially turns nine months old.”

This was greeting by a smattering of obligatory applause and some light woohooing.

“To mark the occasion, Chef Brian has prepared some specials for today’s lunch menu. Chef Brian?”

Chef Brian—an enthusiastic-looking man with dark circles under his eyes—stepped to the fore.

“Thank you, Mr.—I mean, Harry! Yes, in honour of this momentous occasion, we have a special birthday starter. It’s a pasteurized, virtually uncooked take on chawanmushi, served in a nest of lightly wilted romaine. It’s called, ‘Sans chawan sans mushi.’”

Here, Harry interrupted. “The egg symbolizes birth! Don’t you just adore it?”

Everyone attempted to look enthusiastic as they nodded in response.

“Our special birthday main,” Chef Brian continued, “is a slab of pink chicken-breast ‘sashimi’ coated in a blanched-almond tandoori-spiced crust and drizzled with a mint-yoghurt sauce—pasteurized yogurt, of course.”

Harry frowned. “So, where’s the birthday element? I thought we discussed this.”

A look of panic crossed Chef Brian’s face. “I thought we agreed that an obvious birthday element would be too gauche.”

“Did we? I thought we agreed the opposite.”

There was a long pause. “I…can drizzle the yoghurt sauce in the shape of a figure nine,” Chef Brian offered.

Harry pressed his palms together and raised his fingers to his lips in concern. “Do you think that’s enough?”

“I…can add a birthday candle.”

Though Harry didn’t smile, he nodded. “Not as subtly symbolic as the birthday starter, but yes, I think that will be sufficient.”

Chef Brian gave a silent sigh of relief.

“Needless to say,” said Harry addressing all the waitstaff, “make sure you know these specials by heart so you can recite them to our guests in an organic, unstudied fashion. And I’ve noticed that some of you have become lax about directing our non-regulars to the informative welcome page in our menu. Please don’t forget. It communicates our ethos, so they can fully understand and appreciate what a truly life-changing experience we’re creating here. Got it?”

Once again, everyone nodded.

“Good. We open in three minutes. Shepherds to your stations!”

Everyone scurried to take their places, except for Harry, who opened the menu to the welcome page and lovingly reread for the umpteenth time the text he himself had so artfully composed to convey his restaurant’s vision:

Welcome to Pasteural!

In the depths of our name, you will find the seed of our ethos, which, like a real seed, is dense and nutrient-rich. Our name is derived from the French word, “pasteur,” which means “shepherd.” It is etymologically related to the English words, “pastor,” pastoral,” “pasture,” all of which derive from the Latin word meaning, “to feed.”

Indeed, we at Pasteural see ourselves as your shepherds—caring for you, tending to you, nurturing you, nourishing you, providing you with the lush green pastures of unique cuisine on which you can graze. You’ve started a new life in the relatively unspoilt natural surroundings of the More Known World. You deserve the food to go with it.

Our name is also inspired by the surname of Louis Pasteur, the father of the modern food sterilization technique known as pasteurization, in which foods are heated at the lowest temperature required to eliminate harmful pathogens without affecting the quality or flavour of the food itself. Here at Pasteural, we use exclusive, state-of-the-art pasteurization technology and techniques (not found anywhere else) to ensure our dishes are safe to consume, yet for all intents and purposes, raw in appearance and taste.

In short, we are pleased to bring you Nature, but without the danger. Bon appétit from my spirit to yours.

Warmly,

Harry Jones

Founder of Pasteural

Harry smiled and retired to his office so he could enjoy surveilling the dining area and kitchen on his security-camera screens. These past few days, he had been especially gratified to watch the new hire at work. The transformation of whatshisname from awkward, uncoordinated individual to dignified, graceful waiter was truly a testament to the naturally nurturing work environment that he, Harry, had created, which no doubt brought out the best in all his employees.

Murgatroyd, on the other hand, knew better. As he draped serviettes across laps and filled wooden goblets with sparkling water, as he rattled off the day’s specials with greater fluency than he ever spoke otherwise, he knew that what he was experiencing was merely an automatic reversion to a slavish state—a time when he had sought hard to please his employer, his best friend, his parents, everyone but himself. But there was nothing to do now, but endure it and collect his desperately needed pay.

“Psst. Mr. Floyd.”

Murgatroyd turned around to see the bespectacled Settlemore employee who had approached them in the tea tent and escorted them to Winston’s office.

“Oh! Erh, hello. Can I—can I help you?” Murgatroyd stammered, thrown momentarily off-balance by the coincidence.

“Yes, if you don’t mind. May I know…is the sparkling water free?”

Murgatroyd shook his head.

At this news, the man winced. “Ah, I should have asked first,” he sighed, peering with new reverence at his goblet.

“Erh…sorry,” said Murgatroyd, not knowing what else to say.

“It’s okay. It’s okay,” said the man, though he sounded as if he were reassuring himself rather than Murgatroyd. “I’m supposed to be splurging. This is my special birthday treat to myself!”

“Oh! Happy birthday…”

“Choon Yong.”

“Ah. Happy birthday, Choon Yong.”

“Thank you!” replied Choon Yong. He proceeded to look expectant, waiting to be asked the obvious follow-up question.

Murgatroyd obliged. “How old are you?”

“Forty!” declared Choon Yong proudly, before his face turned suddenly aghast. Announcing the figure seemed to have unexpectedly deflated his birthday joy.

“Erh, it’s Pasteural’s birthday too,” said Murgatroyd.

“Really? How old?” asked Choon Yong, attempting to perk up.

“Nine months.”

Choon Yong frowned. “So…the restaurant celebrates its birthday every month? That doesn’t make sense.”

Murgatroyd shrugged neutrally, even though he had to admit Choon Yong had a point.

“So, Mr. Floyd, if I may ask, what would you recommend as the best dish on the menu? The most worth it, I mean.”

“Do you like sashimi? Our birthday special main course is a chicken-breast sashimi.”

Choon Yong stared at him in horror.

“Or…our practically-steak-tartare is popular.”

“How come ‘practically’?”

“Steak tartare is raw beef and raw egg. But we cook it at a low temperature so that it kills all the germs, but looks and tastes raw.”

Choon Yong repeated his horrified stare. “Is there anything you serve that is more… cooked?”

Murgatroyd felt very sorry for Choon Yong, who had obviously not done sufficient research on his birthday restaurant of choice. “You could try the phaux phở,” he said pointing to the corresponding entry on the menu. “It’s almost like real phở, except there are no noodles. Only blanched bean sprouts. And we serve it lukewarm so you can appreciate the slimy—erh, silky texture of the meat. But the broth is quite good!”

Choon Yong tried to smile. “To be honest, I was hoping for something more…exotic,” he said. “French or something. You know, since it’s my birthday.”

He stared at the menu for several seconds more.

“What about these?” he asked, pointing at the description of the bratwurst. “Do these taste cooked?”

When Murgatroyd shook his head, Choon Yong sighed. “Okay, I will have the faux phở,” he said, passing Murgatroyd his menu, trying his best to smile.

Murgatroyd decided to refrain from asking the question that he might have asked another diner at this juncture—Would you care to order something to start as well? As he went off to the kitchen to convey the order, he couldn’t help but sneak a backward glance. He watched as Choon Yong straightened his back, looked around, and took a deep breath, as if attempting to inhale into his very bones the expensive birthday experience he had decided to gift himself. He observed as Choon Yong took a deliberate sip of sparkling water, and, as if he were tasting a fine wine, swished it around his mouth before swallowing. And his heart sank a little when Choon Yong gazed at the young, attractive, well-dressed couple to his left, clinking flutes of champagne and laughing elegantly. The birthday boy turned his gaze down at his own self, as if freshly and painfully aware that his was a table for one.

As Murgatroyd forced himself to turn away again, something stirred inside him, though he didn’t even register it. And even if he had, he would have mistaken it for sympathy, or pity, or simply one of the many sadnesses that drifted inside him and stung him with their tentacles every now and then. Who could blame him, really? How can someone in constant pain all over be expected to detect the appearance of a new discomfort? No, Murgatroyd was not at fault. Not now, and not the several times prior to this, when what was about to occur had occurred.

And neither was he to blame for the next steps he took, which only exacerbated the problem. He asked the waiter technically assigned to Choon Yong’s table if she wouldn’t mind swapping. When serving Choon Yong one of Pasteural’s signature par-baked dough balls, he selected the most done-looking one in the basket. And when he set the faux phở before Choon Yong, he provided a detailed explanation of how special each ingredient was and how unique Chef Brian’s pasteurization techniques were—to make Choon Yong feel better about spending the equivalent of ten food court meals on a tiny mound of bean sprouts and technically-not-raw meat in tepid broth.

Murgatroyd continued to lavish his waiterly prowess—his only prowess—on Choon Yong, checking up on him more than usual, making conversation, listening to the tragic tale of how Choon Yong’s fiancée had died thirteen years ago, two days before their wedding, and how he had never been “lucky in love” since. He learned that Choon Yong had decided to take a job with Settlemore and relocate to the More Known World after the death of his parents because Singapore was too expensive and he thought he might as well try something new. He learned that Choon Yong now regretting trying something new because the More Known World was turning out to be very expensive as well, but he didn’t have the energy to quit Settlemore and attempt resettling in Singapore again, plus he had used all his savings to pay off his late mother’s gambling debts.

And all the while, Murgatroyd remained unaware of the intensifying chemical reaction that was taking place inside him—or at least, it would have been called “chemical” if it had been within chemistry’s scope to document and describe what was happening. It was perhaps most akin to the experience that an Oddfit underwent when discovering and accessing a new Territory—a sudden tug, followed by a slackening of a string and the contents spilling out; a neatly stacked deck of cards collapsing and spreading outward; a melting of ice.

The other times Murgatroyd had accidentally unfolded someone, the only one who’d seen what he’d done had been him. The first incident had been many years ago—an isolated event, and over time, he had grown to disbelieve it had happened, dismissing it as a fear-induced hallucination. But then, a few years ago, when he’d started waiting tables again to earn money, it had happened again, out of nowhere. He’d set down a plate of wonton noodles in front of a woman, and the next thing he knew, there were two dozen of her, at various ages, asking him for a saucer of pickled green chillies. Again, no one else had noticed, but because he had screamed in terror and called for help in putting her back together, he’d been fired on the spot.

Several months later, it happened again, and Murgatroyd had reacted in the same way. Again, he’d been fired.

The next time, he had tried to pretend that nothing was wrong, but couldn’t help trying to walk around the multiple iterations of the person he had unfolded. He had spilled scalding hot soup all over another diner, which not only got him fired, but resulted in him having to pay the doctor’s bills for the treatment of the resulting burns.

The two times after that had occurred in quick succession, with him successfully pretending that nothing was wrong in the slightest—that is, if staring into space, silent and frozen, could be considered “successful.” This was what had happened at The Obese Mouse, and when Murgatroyd had been called into his boss’s office to be let go, he had also been given a lecture on the ruinous effects of taking drugs.

And now, less than a week later… Not again, thought Murgatroyd, armpits suddenly drenched in sweat. He concentrated on keeping his hands steady as he placed the small steam-pasteurized whole-almond “birthday mound” on the table. He had coaxed the pastry chef to assemble it, saying it was a treat for a friend. The plate landed safely in front of Choon Yong. The candle’s flame flickered, but didn’t go out. Murgatroyd began taking quick deep breaths.

“Wah, thank you, Mr. Floyd,” breathed Choon Yong, his voice trembly, his edges shaky, all his features blurring. Then a baby arm popped out above his left shoulder and he grew an extra head—a teenage one with an acne-studded forehead. Both heads suddenly looked alarmed.

“Erh…sorry to ask, but is it free?” they chorused.

A third head appeared, equally anxious-looking.

“Yes, yes, free,” squeaked Murgatroyd, breathing even faster. He took a step back. “Erh, please enjoy. I’m just going to…erh…the toilet.”

And then something happened that had never happened before. As Choon Yong unfolded, shooting out into an enormous unwieldy dragon’s tail of Choon Yongs, he sent his table flying into the artificial lake, along with Murgatroyd.

“What’s happening???!?” cried the Choon Yongs in unison, swinging across the restaurant floor, flinging chairs and tables and screaming diners in all directions.

Harry came running out of his office just as the Choon Yongs turned to Murgatroyd. “What did you do to me, Mr. Floyd??!?” they exclaimed.

“Murgatroyd, you did this??” yelled Harry.

“You—you can see it too?” sputtered Murgatroyd from the lake.

“Of course, I can see it! It’s destroying the whole restaurant!”

Harry yelped as a Choon Yong in his twenties sideswiped him, sending him sprawling.

“Stop it now!” cried Harry, raising himself on his elbows.

“I can’t!” cried Murgatroyd, trying to scramble out of the lake to the safety of kitchen doorway.

It was then that the ground began to shake.

The screams were deafening. The Choon Yongs, too, began shrieking in terror, a chorus of fear. Murgatroyd crawled under the nearest upright table and squinched his eyes shut.

And then, it was all over. Murgatroyd opened his eyes to see other people slowly emerging from where they had taken shelter. Choon Yong had returned to his singular self and was patting his body, as if to make absolutely sure he was back in one piece. Harry was sitting up, speechless and stunned.

Murgatroyd ran over to him. “A-are you okay, Mr. Har—I mean, Harry?”

Harry turned. He saw that it was Murgatroyd. “Get out,” he shouted.

“I promise it won’t happen again, I’m sor—”

“I said, GET OUT!” Unsteadily, Harry tried to rise to his feet. “And if insurance doesn’t cover this, you will!” he mumbled. “Do I make myself clear?”

Murgatroyd turned paler than he already was. “But I don’t have enough money,” he squeaked.

“I don’t care!” thundered Harry, now fully recovered and wholly irate. “Get out and don’t you ever come back!”

“Yes, sir. I mean, Harry. I’m so sorry. Forgive me,” babbled Murgatroyd before exiting the restaurant.

He ran back inside. “Just getting my things!” he apologised, trotting to the kitchen where he retrieved his clothes and flip flops before heading back out. He changed near the topiary signage amidst the hedges, folded his work uniform and sandals, and left them in a neat little pile. Murgatroyd’s intention was to head straight back to his flat—for where else was he to go?—but just as he was about to leave the mall, standing there, at the threshold between the visibly artificial and the artificially invisible, his legs suddenly developed a wobble, lowering his entire body to the floor. He crawled over to one of the potted plastic plants flanking the exit. Under the shelter of its synthetic leaves, he hugged his knees to his chest and let the magnitude of what had just occurred sink in. He had not only unfolded someone yet again—this time it hadn’t just happened in his head. Everyone had seen it. Everyone had felt it and almost been hurt by it. Furthermore, he had caused an earthquake. He stared down at himself in horror. What’s wrong with me? What have I done? He began to shiver uncontrollably.

Something landed on his shoulders. Something soft. He looked up. To his astonishment, it was Choon Yong—just one of him, no more. He had just draped a navy-blue cardigan over Murgatroyd’s shoulders.

“Sorry, you looked cold,” said Choon Yong, awkwardly, kneeling next to Murgatroyd. “I hope you don’t mind. It’s mine. I wear it at work. The AC is very strong in Settlemore Tower.”

Too astonished to speak, Murgatroyd put his arms through the sleeves and wrapped it around his chest. He stopped shaking. The pair of them remained silent for a while.

“Are…are you okay, Mr. Floyd?” asked Choon Yong at last.

Murgatroyd couldn’t say yes, but he felt bad about saying no. What right did he have not to be okay? If anyone wasn’t okay, it should be the person whose being he had just spread across an entire room—yet who was here, crouching beside him, comforting him instead of vice-versa.

Choon Yong cleared his throat and spoke again. “Erh, Mr. Floyd. If I may, I’d like to say thank you.”

Murgatroyd stared. The words finally came: “Thank you? For what??”

A look of confusion came over Choon Yong’s face. “I’m not sure exactly,” he stammered, “but I feel a lot better now. After you…did that thing.”

Murgatroyd stared even harder. “Come again?”

Choon Yong turned red. “I don’t know why I feel better, but I do,” he insisted, trying to articulate his experience the best he could. “I mean, you were being so kind to me during lunch, and that was nice. But after you…erh…stretched me out and put me back together…” (here his embarrassed blush suddenly bloomed into a joyful flush) “I just feel better. Much better! So, thank you!”

Upon uttering these words, Choon Yong seemed embarrassed anew. “I’ll go now,” he said quickly. “I should get back to work.”

Murgatroyd began to take off the cardigan, but Choon Yong stopped him.

“Please, Mr. Floyd. Keep it. I have another one in my desk drawer.”

Then, Choon Yong hurried away, leaving Murgatroyd even more astonished and confused about what in the worlds he had just done and how.

If only he had known that the answer to “how” was tucked inside his wallet, on a scrap of paper. He had been carrying it around with him for years, that tail-end of a longer missive never found, cherished for sentimental reasons, scrawled by Uncle Yusuf himself as he had drawn his final breath. What he didn’t know was that it was the whole message—an instruction for Murgatroyd to do what he did best:

Love,Uncle Yusuf